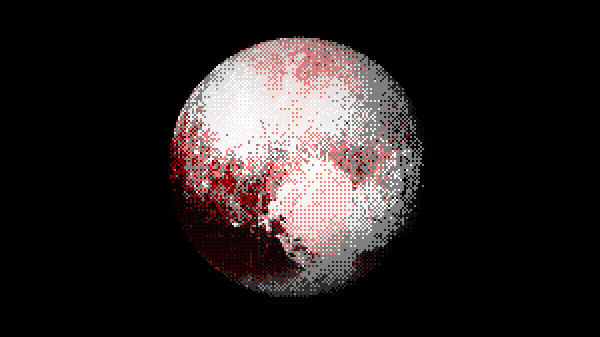

Despite it being smaller than Earth’s moon and receiving about one thousand times less sunlight, images of Pluto taken by the New Horizons mission in 2015 revealed it to be one of the most energetic locales in the outer solar system. And it seemed like Sputnik Basin, a vast icy crater, was its heart.

Sputnik’s stubborn position at Pluto’s equator suggests that something massive lurks below its surface. Planets like to bulge outwards near their equators, so an indentation twice the size of Greenland should force Pluto to reorient its spin to bring the relatively light crater towards the poles. Previous work has suggested that a vast underground ocean pulls the basin to the equator, or perhaps the remnant of an ancient metal asteroid. However, a new paper from Samantha Moruzzi and her collaborators complicates this story – Sputnik seems not to have too much mass, but too little.

While much of Pluto’s surface is as cratered as our moon’s, Sputnik appears as smooth as skin, pockmarked with icy cells. Here, runny nitrogen ice bubbles up from underground, filling craters and surfacing clues about Pluto’s unexpectedly energetic interior. But photos can only reveal so much. Without measurements of Pluto’s gravity field, the thickness of its icy shell (and the mass of whatever lies beneath) remains a mystery. To dig deeper into Pluto’s geologic past, Moruzzi and her collaborators needed a new approach.

If Pluto’s field of nitrogen ice flows as easily as expected, then it should cling to the surface in a predictable way. On Earth, for example, sea level is not quite level – dense regions below the crust cause the ocean to bulge in and out, following a surface of constant gravity. Measuring the peculiar shape of this “geoid” has occupied scientists and surveyors for centuries, and now orbiting satellites have made it possible to determine the shape of Earth’s gravity field directly. New Horizons didn’t bring along a gravimeter for its brief flyby, but by observing the “sea level” of nitrogen ice in Sputnik Basin, Moruzzi was able to reveal the density variations below Pluto’s crust – and rather than the expected mass excess, she discovered a mass deficit. Pluto’s geologic history just got a lot weirder.

In the researchers’ new model, the violent impact that carved the basin did little to disturb Pluto’s balance. The newly thin crust of the crater was supported from below by dense ocean water. As the basin filled with a trickle of nitrogen ice, this buildup of mass forced Sputnik towards the equator, its current home. Finally, the underground ocean froze back into ice, becoming less dense than its surroundings and lightening the load beneath the crater.

These complex dynamics have huge implications for subsurface oceans on other icy bodies, such as the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, whose hot inner cores may fuel explosions of life. Moruzzi shows that even limited data can hide a wealth of information – an image of the crust may be enough to reveal what is beneath.